Radiant As the Moon: Mah Laqa Bai ‘Chanda’ and Visual Culture in Asaf Jahi Hyderabad

- Akshaj Awasthi

Introduction

“katey hai dam ye jo ‘Chanda’ ka yaad-i maula mein

giney hain ‘umr mein apne voh hi shehaar ka din”

“Only if Chanda passes each breath remembering ʿAli’s name

Does her life count and the passing time becomes a day.” (Kugle 2016, 217)

Mah Laqa Bai ‘Chanda’ (1768-1824) represents one of the most enigmatic and prominent courtesans in the course of South Asia’s ‘long’ eighteenth century (Khera 2020, 6).1 While the appearance of courtesans as important figures of power in this time period is widely documented, I examine her status as a recurring character in the Asaf Jahi court of Hyderabad in this historical milieu. This essay, therefore, turns to her appearance in the visual culture of the period, and also explores the functions of the painted portrait in the late eighteenth century Deccan. Examining Mah Laqa’s portraits in the guise of the ragini —the iconic form of sonic modes in Hindustani classical music—found within Khushhal Khan’s illustrated Rag Darshan (composed c. 1808), I draw a narrative linking other dispersed portraits of her to understand her agency in the public realm as a courtesan, and a non-pardahnashin (unveiled) woman. Through my reading of these paintings, I problematise Mah Laqa Bai’s active participation in the courtly public sphere, particularly her repeated identifiable presence in Asaf Jahi paintings which, much like other traditions of the South Asian arts of the book, normally portrayed women and feminine-presenting figures in an idealised manner without physiognomic specificity.

The portrait in South Asia

Before discussing Mah Laqa Bai herself, however, a brief understanding of portraiture in South Asian art is necessary, where recent scholarship has moved beyond a primarily Eurocentric idea of the genre. In the context of early India, Vincent Lefèvre has expressed a willingness to re-define the portrait to constitute a three-fold set of criteria: “intention, perception, [and] function” (Lefèvre 2018, 34). That is, whether the image was intended to represent a historical figure, acknowledged as such (usually through the inscribing of text) as well as being used as a portrait. In early South Asian literary sources, this idea of correct usage refers to the painted or sculpted image carrying the essence of its inspiration, or ‘sitter,’ in the European sense (2018, 41). One such text, the Sanskrit Citrasutra of the Vishnudharmottara Purana also mentions rough counterparts to naturalism and mimesis: anukriti (imitation) and saadrishya (resemblance) (Mukherji 2001, xxxiv). The tradition of portraiture within the Persianate context has also been studied at length by Islamicists, such as Priscilla Soucek, highlighting the importance of ilm al-firaas (physiognomy) in medieval Islamic thought (Soucek 2000, 104). This would evolve during Safavid and Mughal rule towards the notion of painted images evoking an individual’s maʿni (essence) through a masterful depiction of their sura (outer form) (2000, 106).

In South Asia, the portrait often appears melded with the genre of the ragamala, usually a series of paintings evoking a specific raga’s mood, or bhava. Rulers of key northern Rajput courts such as Bundi, Amber and Nurpur increasingly inserted themselves into the mould of the Sanskritic nayaka, or hero, in paintings of the ragamala (Glynn 2018, 125).2The famous set of the 1591 Chunar ragamala (fig. 1), painted by former members of the Mughal atelier under Bundi patronage is a prime example of this (Glynn 2018, 126; Gulbransen 2017, 169–70). In several folios of the series, we see the ruler of Bundi transposed into the role of the nayaka, yet retaining his physiognomic integrity in the tradition of portraits aiming for mimesis. The melding of the genre of the ragamala and the portrait may hint towards a different mode of memorialisation than that seen in paintings from historic Mughal court chronicles, previously studied at length by Susan Stronge through illustrations of the Akbarnama (Stronge 2002, 58–85). Such ragamala portraits may have functioned to memorialise moods and bhava through evoking idealised spaces familiar to the courtly rasika, or connoisseur, a term studied by Katherine Butler Schofield in the early modern context (Schofield 2015, 407–22). This is not to create a false binary between Mughal and Rajput painting, but rather to view them on a spectrum between the classical Indic and imperial Mughal idioms, as argued by Molly Emma Aitken (Aitken 2018, 142). It is through this lens of bhava that we turn to our discussion of gendering the portrait.

Women in South Asian Portraiture, Patronage and Iconography

Unlike portraiture of male-presenting figures in the context of the eighteenth-century South Asian arts of the book, portraits of women aiming for verisimilitude are comparatively rare. One of the few studies of portraiture for members of the royal zenana (secluded and screened portions of palaces meant primarily for royal women) has been Molly Aitken’s archival research on the suratkhana (paintings department) records of the Jaipur court. Aitken highlights the agency of Rajput noblewomen as viewers and commissioners of art, especially in circumstances where their individual clan genealogies could be emphasised (Aitken 2002, 256, 262). The Queen Regent of Jaipur in the middle of the eighteenth century, Maharani Chundavat, was an avid commissioner and buyer of works of art, especially of portraits (2002, 263–65). Even more compelling, however, is the types of portraits she collected—mostly of Mughal emperors and Delhi sultans, as well as typified depictions of certain women (some examples being “young lady” or “Muslim girl”). By conforming to Rajput ideals of femininity, pardahnashin noblewomen like the Chundavat Rani attempted to access symbols of power as much as tradition would allow them (2002, 275).

There is, however, a distinction to be made between commissioning paintings and being the subject of portraits. Deborah Hutton has studied the great proliferation of portraits depicting the sixteenth-century queen, Chand Bibi (d. 1599), who at different points of time had been the regent of Bijapur, and eventually ruler of Ahmadnagar (Hutton 2016, 52). Rather than idealised portraits, most depictions favour an established iconography that displays her martial prowess—harkening back to her victory against the encroaching Mughals in 1596 (2016, 58). Hutton argues that these constituted a conscious effort at creating historical memory of a celebrated figure, and would almost certainly have been in demand by collectors.3

These two examples of historic women sponsoring and appearing in portraits differ significantly in their contexts. Where the Chundavat Rani’s power lay in actively collecting paintings while remaining in purdah, Chand Bibi’s prominence appears from her posthumous depictions for a larger network of viewers. Rather than aiming to find a single overarching template of portraiture for women in early modern South Asia, therefore, it may be more productive to examine the specificities of each individual. As Ruby Lal puts forth, it may reveal our own inherent biases in generalising our readings of royal and noble women, by only granting the status of “historical, individual subjects” to rulers and courtiers that were overwhelmingly men (Lal 2005, 217).

Mah Laqa Bai ‘Chanda’: Portraiture, Performance, Repertoire

Having covered a large gamut of portraits and subjects of women, Mah Laqa Bai’s biography and context can now be examined at some length with points of comparison. Chanda Bibi was born in 1768 to the courtesan Raj Kanvar Bai, under seemingly miraculous circumstances.4An impending miscarriage, according to legend, was prevented by the intervention of Imam ʿAli himself, as well as Shah Tajalli ʿAli, the author of the celebrated Tuzuk-i Asafia, a text commemorating the life of Asaf Jah II, NizamʿAli Khan and the city of Hyderabad (Kugle 2016, 153–54). While her family traced its origins to Gujarat, circumstances forced Mah Laqa Bai’s mother and two aunts into adopting the life of courtesans, as opposed to the pardahnashin status they may originally have held as noblewomen (2016, 193–95). The prime minister Aristu Jah’s influence was fundamental in securing a position for Mah Laqa Bai in the court of Nizam ʿAli Khan, where she gained notable popularity (2016, 167–69). One of her most famous patrons, however, was Raja Rao Ranbahadur, credited for being involved in the production of the Pennsylvania codex of Khushhal Khan’s Rag Darshan (2016, 177).

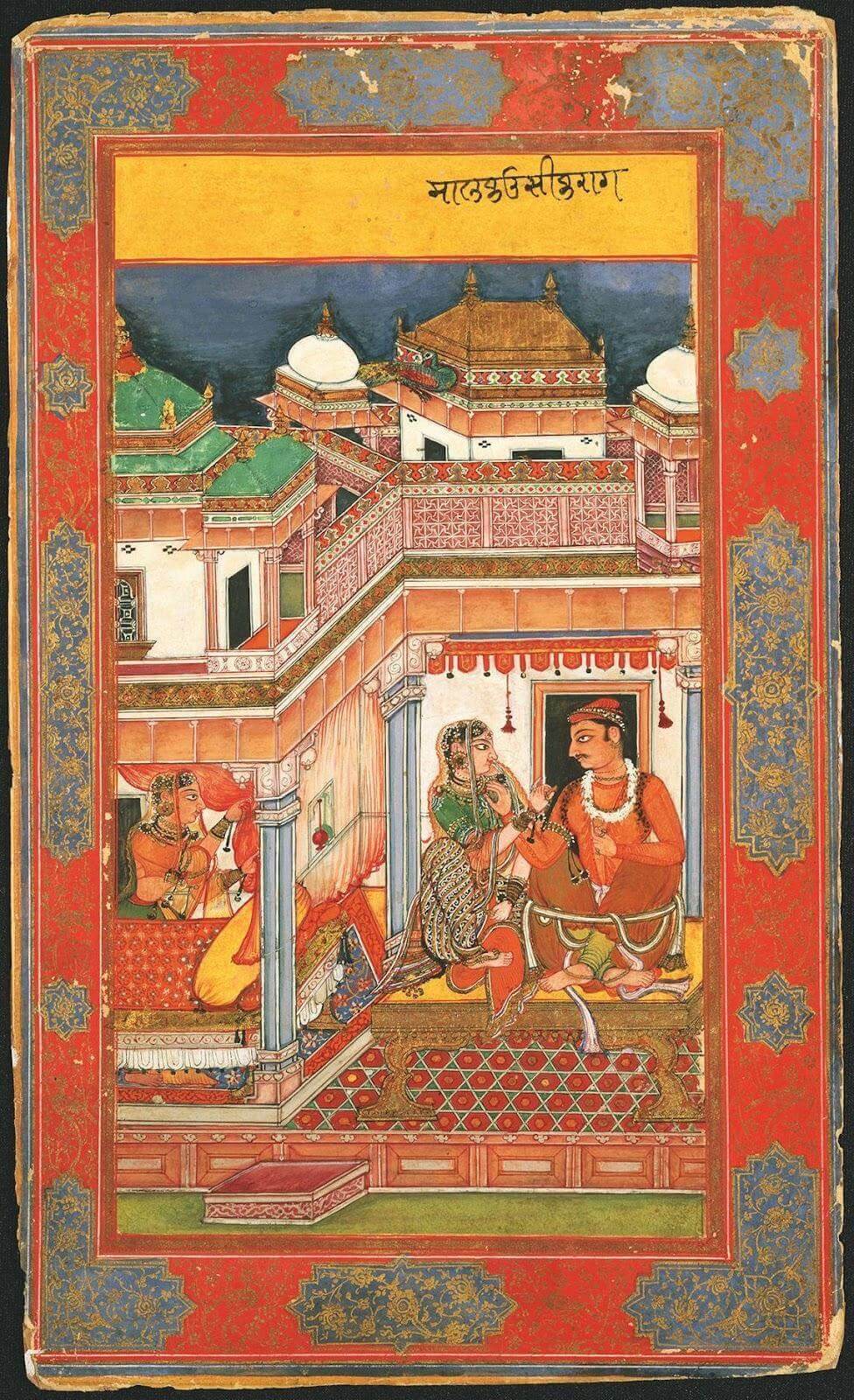

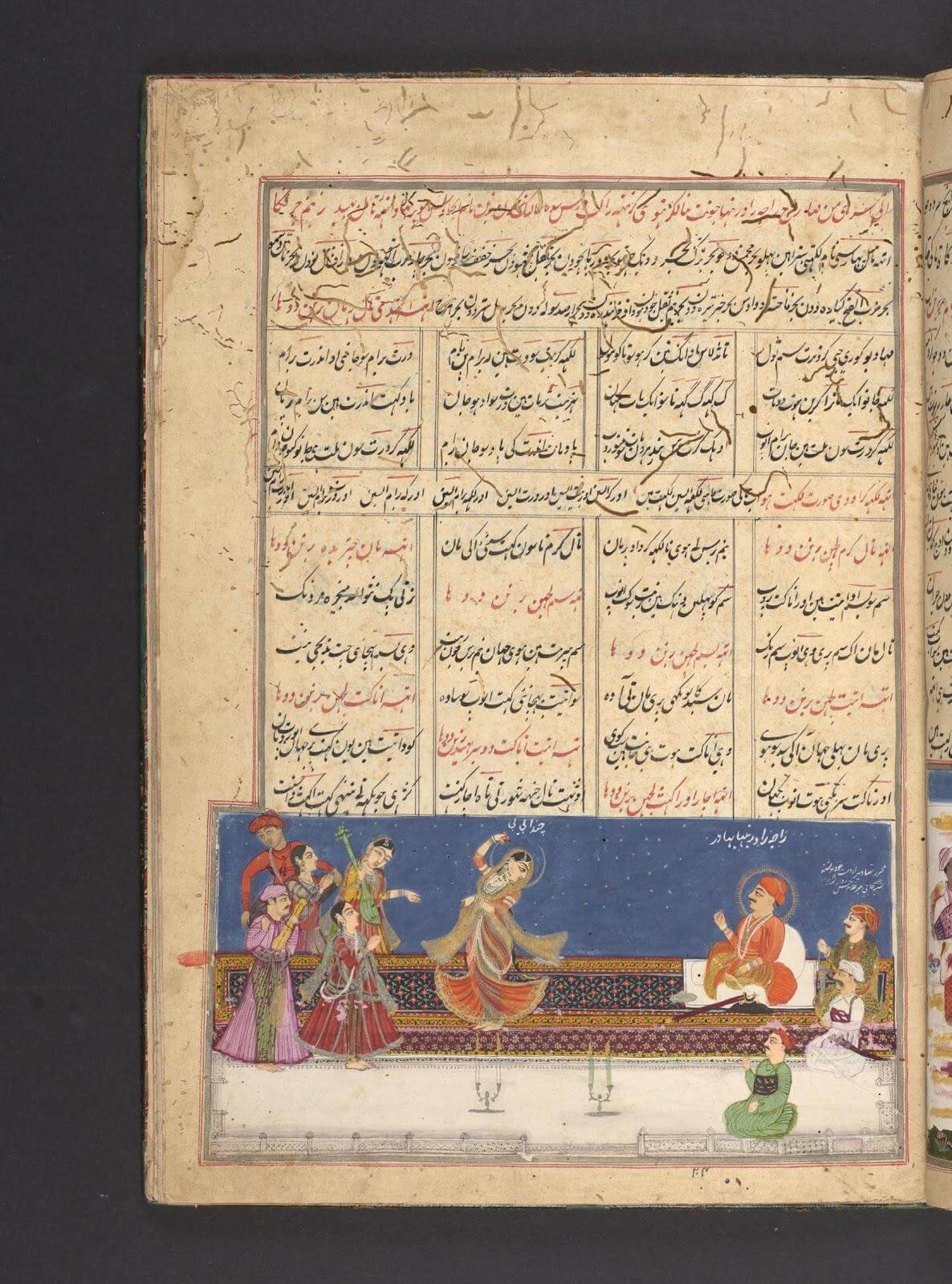

As a woman in the public sphere, Mah Laqa’s presence was more palpably visible than the case of the Chundavat Rani, despite there being indications that the former, too, was an avid patron of the arts (Reddy 2014, 134). This, however, may be linked to the exact nature of the power Mah Laqa Bai negotiated with. As a courtesan, her primary arena was expertise rested in composing poetry, most often in the form of the ghazal, many with devotional themes dedicated to Imam ʿAli, as well as the performing arts of music and dance. This negotiation of power also extended to the visible patronage of buildings—including endowments to sites of Shiʿa veneration dating to the Qutb Shahi period, as well her own palace, the Khas Mahal (Jha 2015, 156). The importance of performance in Mah Laqa’s career can be seen in a surviving group portrait commemorating a gathering at Raja Chandulal’s mansion, or deorhi (fig. 2). A large space before a colonnaded pavilion occupies the foreground of the frame, depicting a large gathering of noblemen watching a performance. Almost all the figures are dressed in rich hues of red or orange, with the majority of the noblemen labelled with names—including several children. On the side of the frame depicting the performance, only one name is explicitly mentioned: that of Mah Laqa Bai herself. With the figures all in full profile, the only person gazing directly at Raja Chandulal is Mah Laqa herself, shown to be larger than the other members of her troupe. The artist’s masterful depiction captures Mah Laqa Bai in the middle of a performance, frozen with one hand raised. This would be an example of bhav batana, an essential element of the tawa’if, or courtesan repertoire, where the lyrics being performed were expounded upon with facial and bodily expressions (Sharma 2021, 53). The painting also hints at the organisational structure of the kotha establishment, a place where tawa’ifs resided. Several younger students and musical accompanists are shown to be present, where the latter group was often dependent on the kotha for their income (Qureshi 1997, 21–22). Unlike the patriarchal framework of the normative heterosexual family, the kotha often functioned as a space where women could be primary controllers of their agency, and at times, enter romantic relationships with each other (Oldenburg 1990, 276). Indeed, the singular emphasis on Mah Laqa as the only woman identified by name in the composition hints at her significant influence within the court, rather than being left unlabelled like the other performers present.

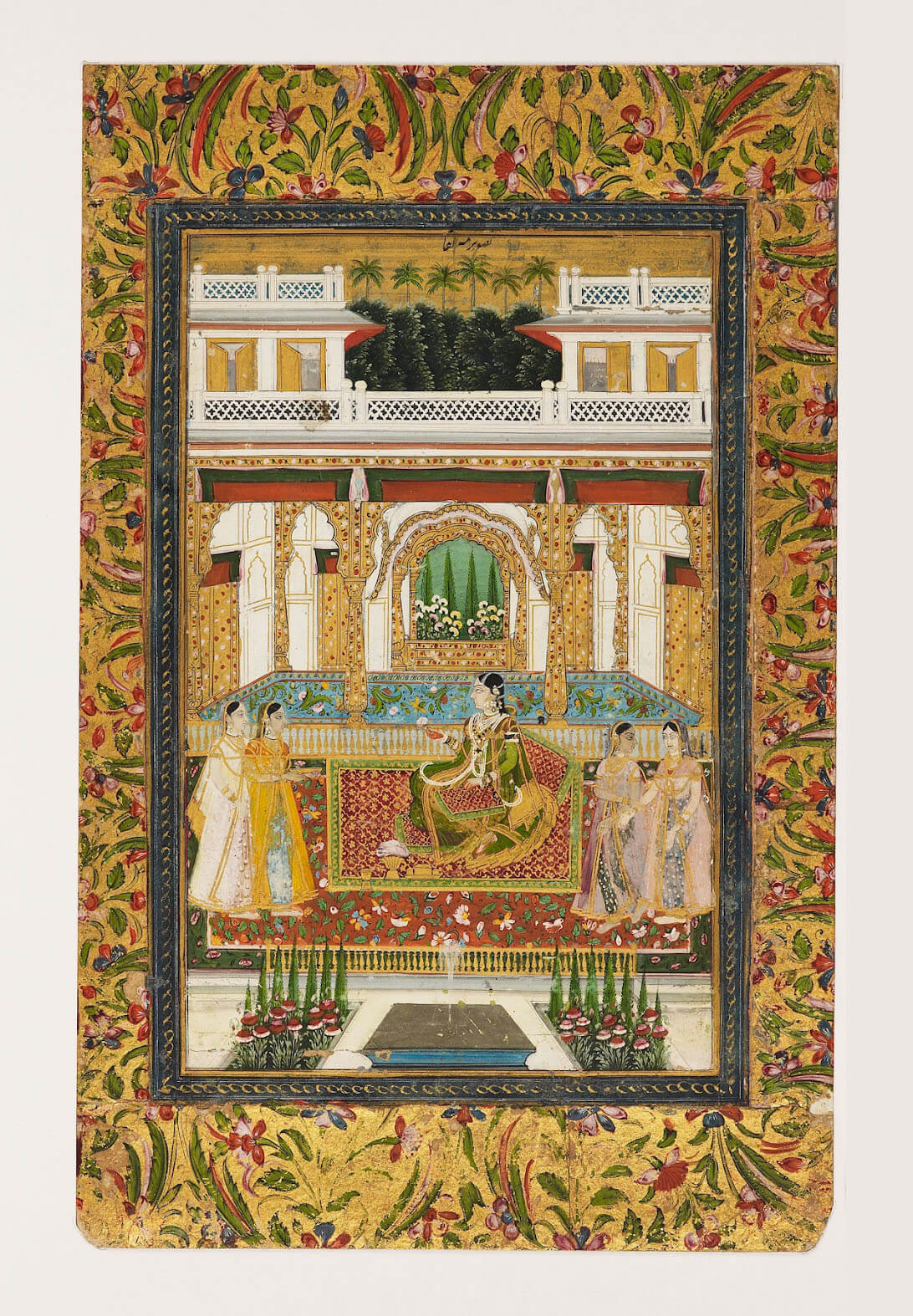

Another painting also depicts Mah Laqa, this time in the relative seclusion of a pavilion (fig. 3). The formal stylistic features of the oeuvre resemble the manner of Rai Venkatchellam—ranging from the ornamented curvilinear bangla, (a style of roof initially popularised in the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s reign) the white buildings, as well as a distant gold-brushed horizon of palm trees in the distance (Koch 2001, 45). While it is difficult to ascertain whether it belonged to the same muraqqa (Persian-style album) as other album paintings attributed to Venkatchellam, the viewer was almost certainly expected to be familiar with the identity of the figure within. 5An inscription on the recto identifies the sitter, stating that it is an image of Mah Laqa Bai (tasvir-i Mah Laqa). At leisure, Mah Laqa Bai sits on a masnad (a cushioned seat of honour) very similar to the one used by Raja Chandulal in the previous painting, and is attended by four ladies in waiting. While depicted in a private space, it initially appears that Mah Laqa Bai was shown to be no different from other idealised paintings of pardahnashin women at leisure. However, the high quality of the work, and its fine use of Venkatchellam’s idiom indicates a higher singular importance accorded to her as an individual.

Rag Darshan and Mah Laqa

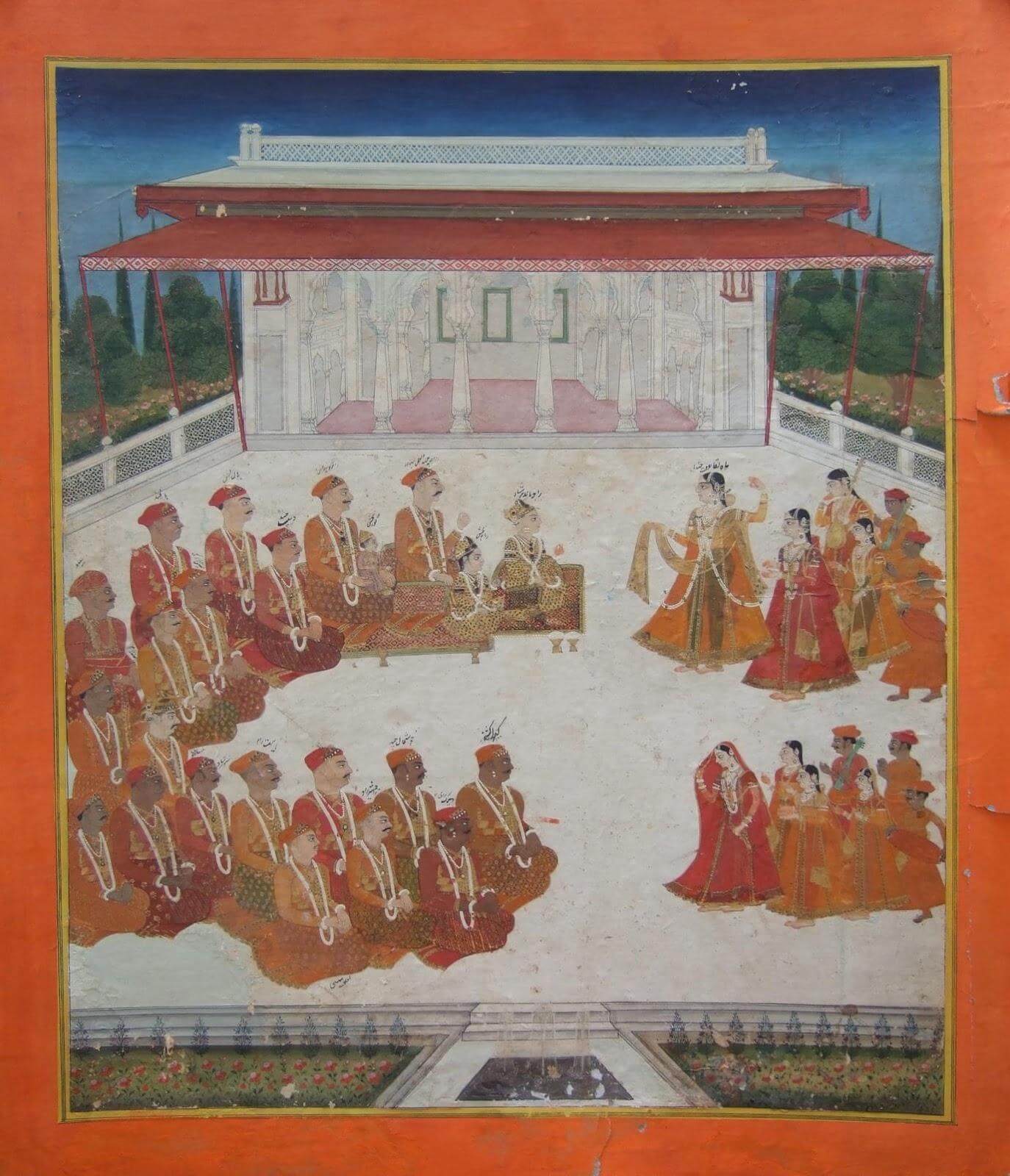

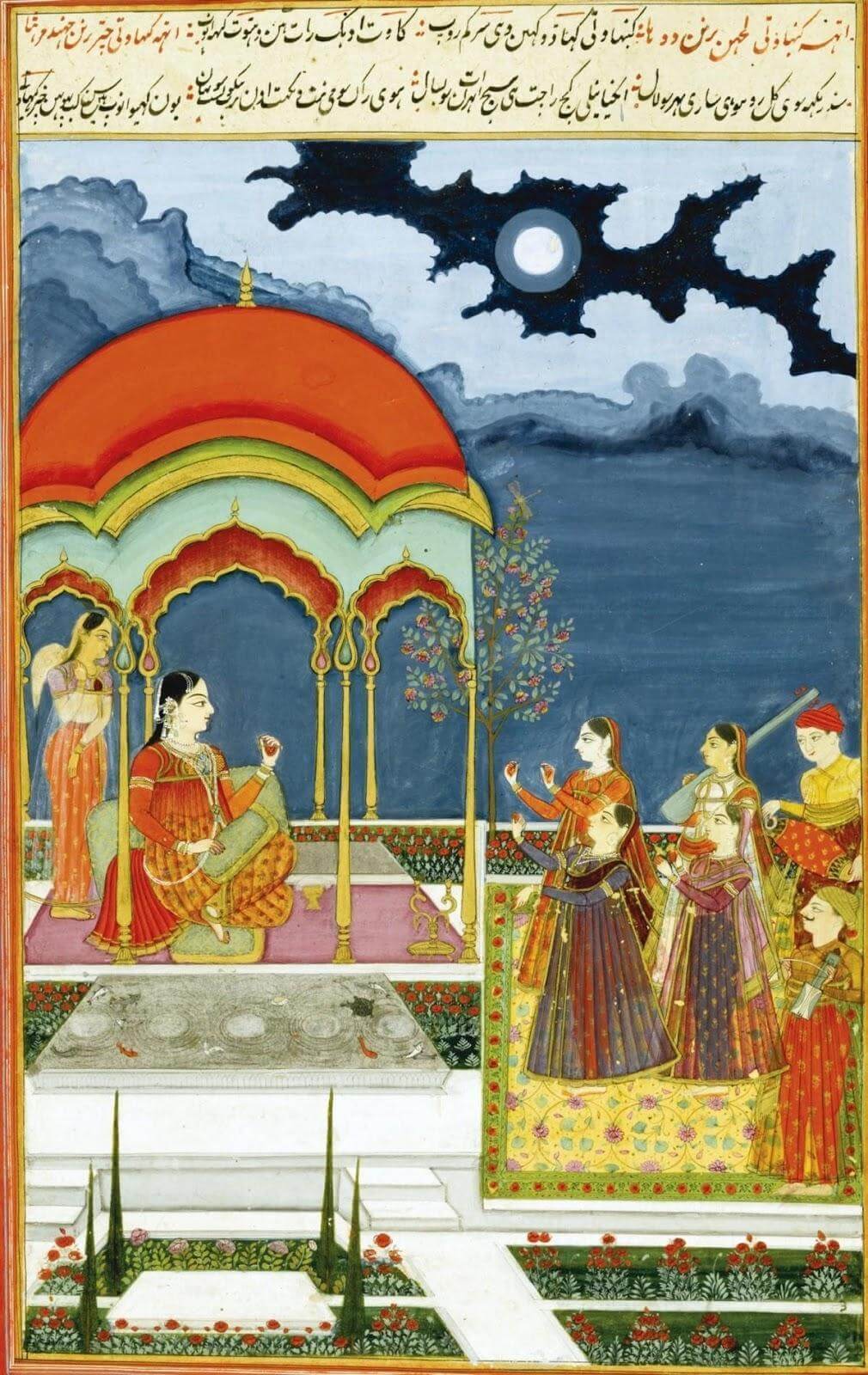

In addition to the single portraits of Mah Laqa discussed so far, some of the finest depictions of her are found within illustrated manuscripts of Rag Darshan —both the Pennsylvania codex, as well as another dispersed set. For these instances, the central role of Mah Laqa Bai in the visual narrative becomes even more apparent. Within the body of the ragamala section in Rag Darshan, Mah Laqa appears as an embodiment of Khambavati ragini (fig. 4), an observation first made by Schofield (Schofield n.d.). Her iconography is consistent with that seen in other folios of Rag Darshan manuscripts—seated beneath a red bangla pavilion, she wears a red angiya (blouse) and watches a performance of other courtesans. The painter of this folio seems to have understood the need to visually transpose Mah Laqa’s title—“like the moon”—a change reflected in the full moon shown in the night sky above. Compared with the single portrait discussed earlier, the format of the ragamala appears to lend itself more easily to showing all aspects of Mah Laqa’s personality. Indeed, with its intense musical associations, one may argue that the depiction of Khambavati ragini functions as a truer portrait of Mah Laqa, especially if the aim were to capture the maʿni (essence) of the subject.

Another painting appears to show a small gathering organised by candlelight in Raja Rao Ranbahadur’s dwelling (fig. 5). The ink-blue hue of the sky behind Mah Laqa Bai is ornamented with stars, but the moon itself forms a halo behind her head. The visual symbolism constructed of Mah Laqa with a lunar nimbus and the Raja with a solar counterpart acts as an emphasis of their relationship. For indeed, who could be more worthy of the company of the courtesan “like the moon” than the sun itself? While the manuscript may have been patronised jointly by the Raja and Mah Laqa, the focus of this folio, and several others, is undeniably Mah Laqa Bai herself—depicted in mid-motion, with her skirts levitating above the ground.

Conclusion

Mah Laqa Bai, much like other courtesans in early modern and later South Asia, mobilised various repertoires of performance, literature, and the visual arts in occupying a public courtly space. Through an art historical lens, this essay elucidates the importance of the portrait in the history of South Asian painting, before expanding into the specific case of women making their presence palpable in the genre. Mah Laqa Bai, unlike many of her precedents from pardahnashin backgrounds, emphasised her performing repertoire publicly as a matter of pride. Indeed, unlike Rajput noblewomen such as the Chundavat Maharani of Jaipur, who exercised power through their relative invisibilisation, Mah Laqa exercised the same by deliberately being in the public gaze.

The character of the courtesan, or tawa’if , suffuses South Asian literature and cinema and has appeared in several forms—ranging from Mirza Hadi Ruswa’s classic Urdu novel Umrao Jaan Ada (‘Ruswa’ 1899), as well as Premchand’s Hindi novel Sevasadan (originally written in Urdu as Bazaar-i Husn ) (Premchand 1919). The performative, visual and material aspects of courtesans inhabiting the public sphere, however, remains a valuable topic of further study—ranging from Kishangarh’s Bani Thani, to Muhammad Shah’s consort, Udham Bai and the inimitable Begum Samru of Sardhana. To someone familiar with Mah Laqa’s repertoire, however, it is not difficult to see echoes of her memory in films such as Shyam Benegal’s Mandi (Benegal 1983)—where women with agency inhabit a kotha in the very same city where Mah Laqa Bai once danced as a ragini under the starry skies near the Mawla ʿAli Shrine.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Preeti Bahadur Ramaswami and Dr Sraman Mukherjee for their constant support while I wrote my capstone thesis, a chapter of which has now appeared in the form of this essay. I would also like to thank Latika Gupta, and Dr. Eloise Wright for their ever-brilliant thoughts on materiality and manuscripts that have greatly informed my research.

Endnotes

- Dipti Khera argues for the ‘long’ eighteenth century to be looked at as the continuum of historical and social developments from the emperor Aurangzeb’s death in 1707 to the 1830s.

- Ironically, the genre of the ragamala was also known for its relative iconographical stagnation during the early modern period, making this shift even more surprising.

- Hutton’s search revealed at least 20 such paintings in collections from the United States and the United Kingdom. As museum digitization processes are still in their early stages, a far greater number is also likely present in other museums worldwide.

- Chanda Bibi was the birth name of Mah Laqa Bai, the latter being granted to her by the Nizam later in her career.

- An example of this is a portrait of Maʿali Mian Saif al-Mulk attributed to Venkatchellam, currently in the David Collection of Copenhagen: https://www.davidmus.dk/islamic-art/miniature-paintings/item/1411?culture=da-dk.

Primary manuscript sources

Khan, K. (n.d.). Rāg Darshan. Unpublished illustrated manuscript. Hyderabad, Deccan, c. -1804 1799. Lawrence. J. Schoenberg Collection, University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

Secondary sources

Aitken, M. E. (2002). “Pardah and Portrayal: Rajput Women as Subjects, Patrons, and Collectors”. Artibus Asiae, 62 (2), 247–80.

—. (2018). “Dark, Overwhelming, yet Joyful: The Monsoon in Rajput Painting”. In Rajamani, I. et al. (eds.). Monsoon Feelings: A History of Emotions in the Rain. New Delhi: Niyogi Books.

Benegal, S. (dir). (1983). Mandi. Blaze Entertainment.

Glynn, C. (2018). “Becoming the Hero: Metamorphosis of the Raja”. In Branfoot, C. (ed.). Portraiture in South Asia since the Mughals: Art, Representation and History. London and New York: I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd, pp. 125–44.

Gulbransen, K. H. (2017). “Reassessing the Origins of the Portrait Genre in Bundi: A Case Study in Northern Indian Artistic Exchange”. Artibus Asiae, 77 (2), 131–82.

Hutton, D. (2016). “Portraits of “A Noble Queen”: Chand Bibi in the Historical Imaginary”. In Aitken, M. E. (ed). A Magic World: New Visions of Indian Painting. Mumbai: The Marg Foundation, pp. 50-63.

Jha, S. S. (2015). “Tawa’if as Poet and Patron: Rethinking Women’s Self-Representation”. In Malhotra, A. and Lambert-Hurley, S. (eds). Speaking of the Self: Gender, Performance, and Autobiography in South Asia. Durham and London: Duke University Press, pp. 141-64.

Khera, D. (2020). The Place of Many Moods: Udaipur’s Painted Lands and India’s Eighteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Koch, E. (2001). Mughal Art and Imperial Ideology: Collected Essays. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Kugle, S. (2016). When Sun Meets Moon: Gender, Eros, and Ecstasy in Urdu Poetry. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Lal, R. (2005). Domesticity and Power in the Early Modern Mughal World. Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

Lefèvre, V. (2018). “Portrait or Image? Some Literary and Terminological Perspectives on Portraiture in Early India”. In Branfoot, C. (ed). Portraiture in South Asia since the Mughals: Art, Representation and History. London and New York: I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd, pp. 33-48.

Mukherji, P. D. (trans.) (2001). The Citrasūtra of the Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and Motilal Banarsidass.

Oldenburg, V. T. (1990). “Lifestyle as Resistance: The Case of the Courtesans of Lucknow, India”. Feminist Studies, 16(2), 259–87.

Premchand, M. (1919). Sevasadan. Lucknow: Pustak Agency.

Qureshi, R. B. (1997). “The Indian Sarangi: Sound of Affect, Site of Conquest”. Yearbook for Traditional Music, 29, 1–38.

Reddy, S. (2014). “Imaging History, Mapping Culture: Visual Culture and Historical Representation in Asaf Jahi Hyderabad”. Doctoral dissertation, New Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru University.

‘Ruswa’, M. M. H. (1899). Umrao Jaan Ada. Lucknow: Munshi Gulab Singh & Sons Press.

Schofield, K. B. (2015). “Learning to Taste the Emotions: The Mughal rasika”. In Orsini, F. and Schofield, K. B. (eds). Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, pp. 407-22.

———. (n.d.). “Eclipsed By The Moon: Mahlaqa Bai and Her Teacher “The Incomparable” in Nizami Hyderabad”. Histories of the Ephemeral: Writing on Music in Late Mughal India. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QW8ZwPq_4ws&list=PLg0HR8BZTkv8lIbEQSQv7Kib0GrWvYtaE&index=1; Retrieved on 3 October 2021.

Sharma, R. (2021). “When Love Was Banished: Historicising Tawa’ifs’ Embodied Performance of Romance And Desire (1860s-1930s)”. Capstone Thesis, Ashoka Scholars Programme, Sonipat: Department of History, Ashoka University.

Soucek, P. (2000). “The Theory and Practice of Portraiture in the Persian Tradition”. Muqarnas, 17, 97–108.

Stronge, S. (2002). Painting for the Mughal Emperor: The Art of the Book 1560-1660. London: V&A Publications.

- Akshaj Awasthi

Akshaj (they/them) graduated from Ashoka University in 2022 with a B.A. in History, followed by a Diploma in Advanced Studies and Research (DipASR) as part of the Ashoka Scholars Programme. This culminated in their Capstone Thesis from the Department of Visual Arts titled Deccan, Forgotten? Hyderabadi Visual Culture in the ‘Long’ Eighteenth Century, an art historical study complemented by Persian and Braj Bhasha sources from which this essay draws. In 2020, they also completed an Undergraduate Thesis in the Department of History titled Power as Patronage, Imperial Art and Architecture Under the Mughals and the Ottomans. They have previously worked with the Ashoka Centre for Translation, and are also a literary translator working primarily from Urdu and Hindi into English. Akshaj’s research interests lie in studying the arts of the book in early modern and medieval South Asia, comparative art historical studies with the larger Islamicate and Asian worlds, as well as the interplay between performance and art history.