As a political category, Indian womanhood appears most acutely through performance. In such performances, which both extend and subvert established norms of gender comportment and sexuality, it becomes possible to understand how womanhood is contested. One of the sites where performance does this kind of political work is cinema. In the Telugu speaking context, womanhood, whether revered and reviled, has been negotiated, defined, and litigated through the bodies of women—variously understood as hereditary performers or “courtesans”—who appear on screen. Importantly, through their appearance on screen such women were often able to either subvert or otherwise obscure their caste identities (see Putcha 2022).

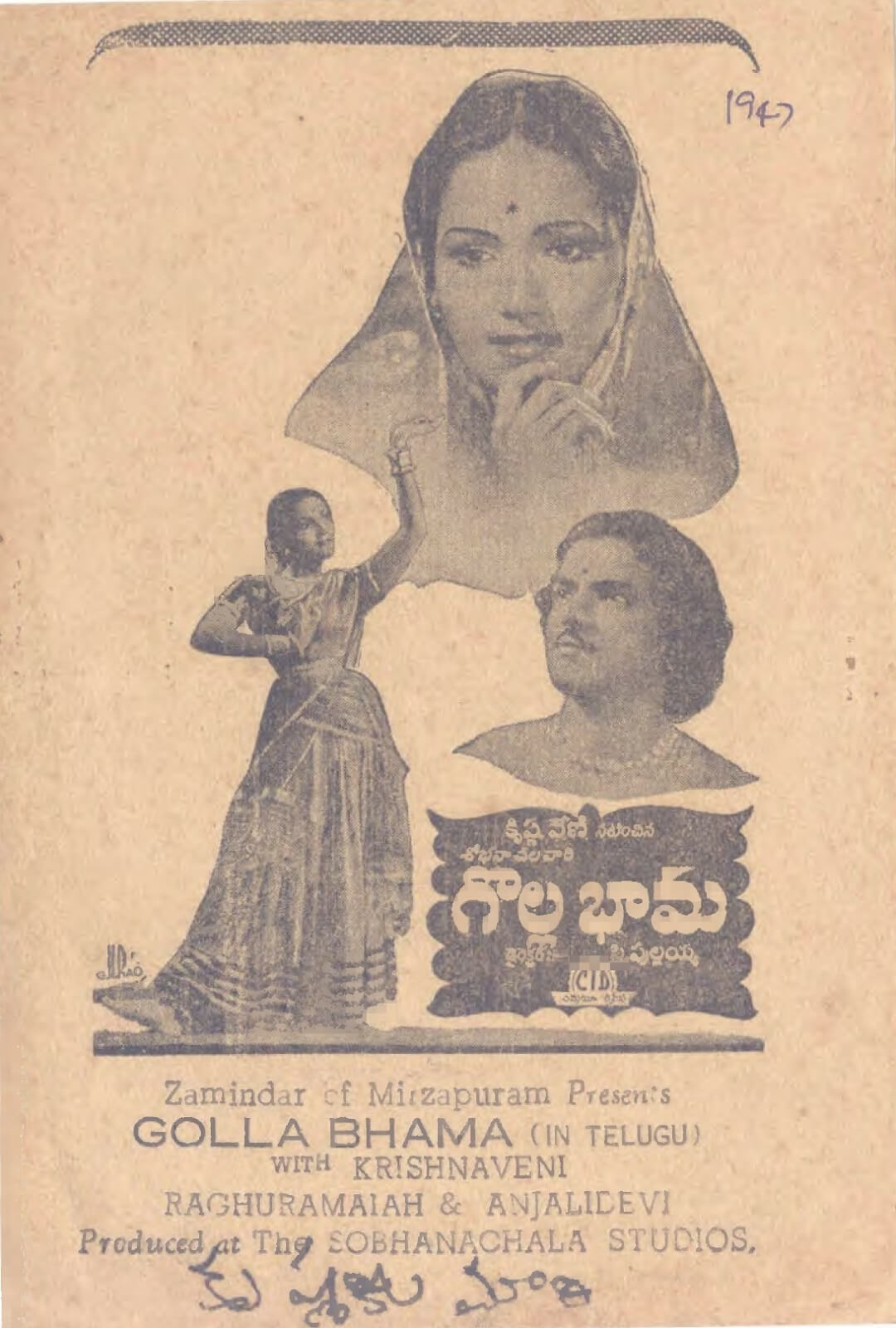

One of the earliest and clearest examples of the way performance allowed and arguably still allows for a blurring of the boundaries between representational and social ideals of womanhood appears in the actresses who appeared on screen as dancers and singers in 20th century Telugu cinema. Beginning in the 1930s, actresses like Chittajalu Krishnaveni (b. 1924), who could trace their music and dance training to their natal communities, had entered the film industry and were shaping public conversations on Telugu womanhood specifically, and Indian womanhood, more generally.

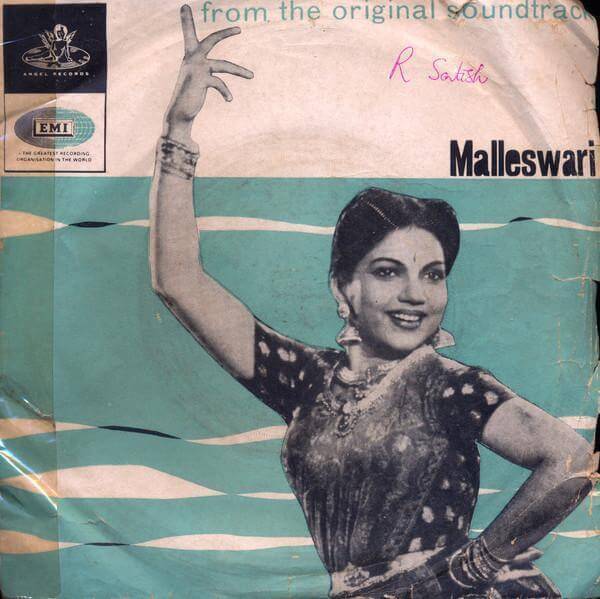

Indeed, in the era immediately following the rise of sound films, an actress with a similar background, Paluvayi Bhanumati (1925-2005), better known as R. Bhanumati, emerged as a Telugu film star. Over the course of Bhanumati’s career, which spanned decades and eras of south Indian cinema, her star power not only shaped notions of womanhood, but also beauty, fashion, and musical citizenship. Bhanumati’s immense influence on Telugu society vis-a-vis cinema and in the early years after Indian independence offers context to the synergies that seem to link marginalized communities and their expressions of gender and sexuality to formations of stardom and celebrity. These expressions can be perceived most clearly through the on-screen song-and-dance sequences, which also circulated into the home through gramophone records and printed songbooks.