Mapping Excesses, Mapping Bodies: Red Dress Waali Ladki, the City and Sexual Violence

- Supraja R.

Red Dress Waali Ladki demands to be held in generous, capacious headspaces, unafraid perhaps of what kind of associations it may bring about, or what kind of searing trace it may leave. Holding, witnessing and sharing space with Diya Naidu, who conceptualized and performed this piece, is not a disembodied participation – one enters the space, but exits changed in some many ways. The show I had been to was on the 23rd of February 2020, just a couple of weeks before the pandemic subsumed living rhythms across the world. It was perhaps one of Naidu’s last performances in Bengaluru as well, right before her months long battle with the virus and this I find, is a sobering thought – that one may have shared one of the few momentous senses communis1 (of a sensorium holding folks together even when apart) before performance (as we have come to know it since) has changed irrevocably.

Reflecting on the looming contagion, climate crisis and rising tempers of fundamentalism across the globe, taking cognizance of a ‘slow violence’ would aid in foregrounding a feminist geopolitics that is called upon in this piece. As Nixon says of slow violence,

[it is] a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.2

How does this link to Red Dress Waali Ladki? In the artiste’s own words: Red Dress Waali Ladki was born out of the artist’s response to the brutal crimes against women in India. Through the research and introspection that went into making the work, she decided to talk about the layered, subtle experience of the woman, who is seemingly liberated but constantly carries fear in her body. Where does this patriarchal penetration locate itself? If her rape is my rape, can my bliss be hers too? Can the men be invited as equals into this?… These are the questions the work raises.

The work is an ongoing (failing) research. Not scientific per se or even just physical. Not even restricted to the laboratory (in this case studio). It will probably never stop. But one can hope. It began in 2014 and now is a non-performance of itself. If you are here to witness, you will in some way carry it.3

The piece is a solo dance-theatre effort. Since first being devised in 2016, the piece has morphed, changed, subtracted and added to its movement, gesture, semiotics and rhythm. Indeed, the kineticization of movement in the piece is something that deserves ample dwelling upon, a non-performance as Naidu has so aptly termed it. The piece holds an intermedial framework – one that straddles contemporary dance, extensive use of voice, breath and theatricality in an interwoven rendition. It is a “sharing”, that throws into light a witnesses’ implication as a neoliberal consumer of sexuality, commodity and gender in a 21st century globalized Indian cityscape.

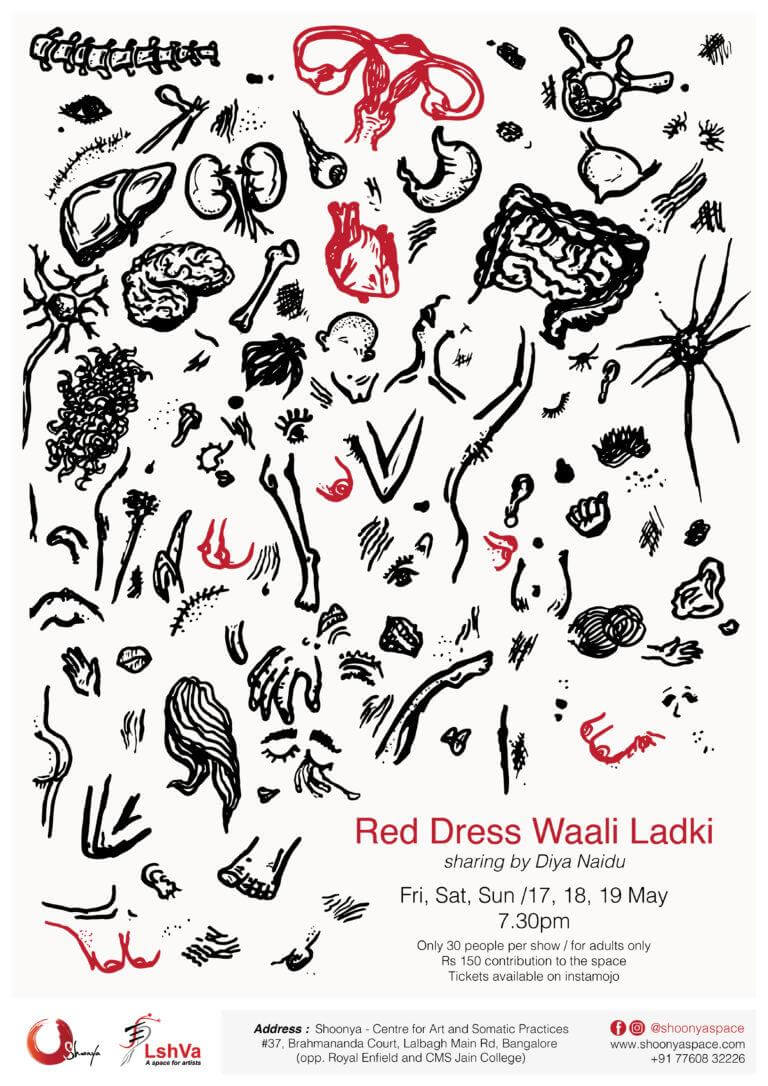

The poster for the piece as noted in fig. 1 is one that is an episteme of its own, an iteration of an interartistic mediation. In it we see doodles of disconnected, singular body parts: some in red, some in black. Organs dismembered from one another, placed in an absolute discombobulated rhythm – seemingly with no pattern as it were. There is a certain manner with which such an objectification seems exposed as a map – a map of body politic provoking the biological determinism of gender and sex. This is amplified by what we encounter: at the bottom left, we see a part of a torso. Here, the breasts are red whereas the clavicle and the reach of the neck are black – this is the only doodle that holds a dichotomy of colour. On the other hand, the uterus and ovaries are red too. The heart, of course, is emblazoned in red. By this poster, one cannot help but wonder if Naidu seeks to foreground this piece as privileging slow violence experienced only by persons with bleeding bodies. The heart holds a pull to the affective – is that why the breasts, and the uterus are in red? The title of the piece too – Red Dress Waali Ladki (RDWL henceforth) – is in the same colour.

The (gendered) scream has been written widely about in both cinematic scholarly debates as well as that of in visual culture/art history. The initial spark of kineticization of the performance combusts through the sculpted posture of fig. 2, the formalism of line extending to a triangular geometricity of both cloth and body – the red arresting our attention as our ears crane for a scream we cannot hear. Behind Naidu we see a clothesline with clips dangling, an integral part of the scenography and of a utilitarian aide in the piece that harkens to the frozen image of the discombobulated, glitched corpus of the poster (fig. 1).

The oscillated feeding of the visceral through the corporeal is where the thrumming rhythm of this non-performance lies. The non-performative quality of the piece lies in the very horrific citational reality of caste and class based sexual violence that is a part of the quotidian fabric of this country.4 The weaponization of a viscerality harkens then to the energy of the performer and the sensus communis so created between them and the spectator(s).5 It is within such a shared space that the excesses of a non-performative de-humanization are pinned on the clothesline, mapping the body, mapping the inhabitants of the city – three personas punctuated into a specific focus.

Again, in the artiste’s own words: The performer is possessed by and channels these characters to conduct a kind of bizarre research in the area of, “patriarchal penetration”. She does this by locating these experiences in her body and constantly sharing her findings with the audience.

– Warrior – a female police officer

– Goddess/ Whore – a diva with her own TV show and website

– Mother/Wife – a housewife

It is interesting to note that each of these three embodiments carry with them an accented style of regional embodiment, as is within a mainstream urban cityscape. Naidu plays with their accents too – we see that the diva speaks to an American-keen consumer base, while the homemaker is discernably from a Savarna suburban habitus. Interestingly, while the latter two personas have their own renditions of accented English, the woman police officer speaks in Hindi, devoid of any coquettishness that largely the latter two emulate, to varying degrees of appropriation.

I would harken here to Kareem Khubchandani’s recent formulation of Ishtyle to highlight this tripartite embodiment. When speaking of the accented coinage of the term, he says that accents are imbued with habitus, acquire “dispositions” that through a discursive and embodied repetition find an interstice with gender, caste, class, race, ethnicity, religion and so on.6 The friction of accented experience that these three personas labour towards are braided and punctuated, drawing our attention to the sensorial logics of “patriarchal penetration” (as Naidu’s frames it) experienced by them in the cityscape they intersect in and inhabit.

For one, the piece throws up questions on honor and agency as being pivotal in the contortion of the social life of the law circulating discourses on rape as delegitimizing [women] and [women’s] sexuality. Naidu’s officer embodies this via registering the wife’s act of masturbation (in the privacy of their own home!) as an offence – as related by the husband. This engages legal cartographies surrounding the politics of pleasure in discourses of marital rape. This is troubled further when we come to question the officer’s agency as sympathetic to the wife’s cause – the former is, after all, a crusader of the state yet deals with daily oppressions in a highly gendered profession. Naidu then throws up the gendered labour of this body in the domestic space in an alienating, visceral manner. This intersects with the diva when we are asked to consider the limits of agency acquired by playing to the drum of a liberated sexuality, as one that is yet vulnerable to intimate partner violence.

These rhythmic personas move within the slow/fast violences of a patriarchal penetration mapped in the piece. As slow forms of violence imbricate with the fast, and the fast inescapably shapes the slow. An intersectional feminist imagination reveals the co-constitution of these temporal binaries. Moreover, as the gradual nature of slow violence reinscribes divisions of public/private and intimate/global by separating the political causes of violence from their embodied consequences, treating fast/slow violence as a single complex provides us tools to challenge the gendered and casteist epistemologies that depoliticize or erase slow violence.7

While in conversation with Naidu a few days after the show, she mentioned that there had been instances where fathers dragged their daughters out, their “good senses” scandalized and mortified by this visceral excess. In my own experience in that liminal space of sharing with my mother and my (septuagenarian) grandmother, I had to push away my own responses to check in on the two of them – specifically, on the latter. She was visibly distressed – and at a certain point I had to remind her of the note we were given prior to the performance – that people were free to leave, but not come back, if they were triggered. But no, she held on and held through by holding hands in bated breath with my mother, whom she seemed to be sharing in strength with, with darting reassuring looks, shifting posture, grasping on to each other’s presences in our twenty-member intimate, combusting communis.

What does it mean when a visceral non-performance presents to us a phenomenological encounter with the cityscape quotidian of gendered violence? From the bottom of the pyramid of rape culture to that of the apex, we see that it is the small acts of the everyday that informs and implicates us all. Naidu’s piece makes a compelling argument for taking cognizance of the manner in which the gender (and sex!) binary needs to be abolished. Ergo, while some may even say that this piece makes a spectacle of violence, I hold that the affectual excess of the piece opens up to a more radical argument on whose bodies violated can be mapped and how, mediated as is through this non-performative telling.

1. Brahma Prakash, “Materiality in the Performance of Cultural Labour: Contemporary Bidesiya in Bihar,” in Cultural Labour: Conceptualizing the ‘Folk Performance’ in India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 131.

2. Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), p. 2.

3. Taken from an email personal correspondence of Naidu’s concept note for the piece.

4. The piece was devised in response to the horrific Nirbhaya case of 2012.

5. Brahma Prakash, “Viscerality: Guts to Perform Dugola,” in Cultural Labour: Conceptualizing the ‘Folk Performance’ in India (New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press, 2019), pp. 177-205.

6. Kareem Khubchandani, “Introduction,” in Ishtyle Accenting Gay Indian Nightlife (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2020), p. 8.

7. As was only yet again very recently done with the Hathras (2020) case.

- Supraja R.

A bricoleur of intersubjectivity, a sculptor of space, art and laying bare vulnerabilities, Supraja R finds their calling within the liminal. They/She are engaged with work primarily through and within theatre and performance, traversing the boundaries and borders of scholarship and intellectual history, strategizing artistic practice in a bid to spark conversations, beyond foreclosing limitations. They have worked in the theatre in varied consistencies and contexts, tussling with the questions of embodiment in space and social positionality, within and beyond the boundaries of the studio floor. Their efforts have never been enough.