Singing Of Shringaar: Negotiating Female Desire In 20th Century Hindi Cinema

- Shirsha Ghosh

In Casablanca (1942), Ilsa makes an impassioned plea to Rick, “Kiss me. Kiss me as if it were the last time.” Leading ladies in Hindi films, unfortunately, are rarely afforded the same frankness and have historically been confined to more subtle means of expressing their longings. The celebration of feminine desire on-screen is rare; rarer still are women who take the onus of their own desires. Gyrating hips or bashful glances, wanton vamps or comically aggressive cougars – female sexuality is constructed on-screen either to echo male fantasies or to be the butt of the joke. Remember Sweetu from Kal Ho Naa Ho?

While male sexuality and male fantasies of female sexuality are veritably normalized, any instance of women expressing their needs and fantasies inevitably raises hackles (and eyebrows). Caught forever between the Virgin/Whore dichotomy, women in Hindi cinema of the twentieth century found the song-and-dance sequence as the solitary site where they could negotiate their desires and fantasies.

The much-maligned song-and-dance sequence—a quintessential fixture of Hindi films since the inception of the talkies—are often considered superfluous interruptions rather than important narrative devices. But when used skilfully, these sequences can be powerful storytelling tools packing a punch that scores of dialogues or lengthy visual scenes cannot match. Take ‘Ek Haseena Thi’ from Karz (1980), for instance. Sure, the song sequence could easily be swapped out for a few minutes of dialogue. But can that ever produce the same dramatic effect that the song sequence delivers?The iconic song-and-dance numbers of Hindi cinema have their origins in ancient Sanskrit dance-dramas and regional theatrical forms such as Nautanki, Khyal, and Parsi theatre. From the traveling Urdu-Parsi theatre troupes of the past to the grand productions of today, the tradition of “singing out stories” has been an integral part of Indian storytelling. Historically, music traditions have often provided a space for women to explore their desires, even in a patriarchal society where female erotic desire is seen as transgressive. A notable example is the Thumri from Hindustani music, which frequently conveyed women’s desires and experiences through sensual and sometimes erotic verses. This tradition of musical storytelling found its way into Hindi cinema and became a cornerstone of the industry.

Song sequences in Hindi cinema often open up a realm beyond conventional narrative constraints. While the primary storyline needs to adhere to logical progression and societal norms, musical interludes are not subjected to the same rigidity. These scenes can whisk characters away to picturesque locales or provide a subversive space where women can confess love and indulge in physical intimacy that would be considered taboo in the main narrative. Songs served as a language for the inexpressible, enabling characters to articulate emotions that might otherwise remain concealed. At times, they publicly declared love, while in other instances, they offered intimate confessions.

It is perhaps only in a song that a demure housewife like Sudha in Ijaazat (1987) can declare “Pyaasi Hoon Main, Pyaasi Rehne Do” (If I’m left thirsty, let it be so) or Sandhya in Woh Kaun Thi? (1964) can say “Lag Ja Gale Ki Phir Ye Hasin Raat Ho Na Ho” (Embrace me, for this beautiful night may not come again) without transgressing the bounds of propriety.

Depicting the nuances of female sexuality and desire proves to be a herculean task for mainstream media that oscillates between the extremes of either silencing women’s desires or commodifying them through ‘item songs.’ Ironically, Indian cinema is nothing if not verbose, with its grand dialogues and long-winded soliloquies. Yet, it seems to falter when it comes to giving a voice to feminine desire. If there is one thing that unites the female characters in Hindi cinema of the 20th century, it is their depiction as almost sexless creatures. This reflects a broader cultural context where sexuality, though central to human experience, has forever been relegated to the realm of taboo. In a society so allergic to discussing women’s sexuality, these song sequences, even when crafted by male artists, became vehicles for navigating the complex terrain of female desire on screen, often featuring symbolic expressions of eroticism without making their puritanical audience seek their smelling salts.

In ‘Aaiye Meherbaan’ from Howrah Bridge (1958), Madhubala sways sensuously to O.P. Nayaar’s music. Though set in a hotel, the song departs from the typical cabaret number, opting for a subtler scene of seduction. Madhubala smiles coyly at Ashok Kumar, likening his gaze to a lightning bolt striking her heart:

Dekha Machal Ke Jidhar, Bijli Giraa Di Udhar

Kiskaa Jalaa Aashiyaan, Bijli Ko Ye Kyaa Khabar

Wherever your playful gaze fell, a lightning bolt struck there

What does the lightning care about whose home it burnt

Both Tanuja in ‘Raat Akeli Hai’ from Jewel Thief (1967) and Nanda in ‘Yeh Samaa, Samaa Hai Yeh Pyaar Ka’ from Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965) dance seductively in silk nightgowns, trying to woo their beloveds. While Tanuja is much more playful and proactive, boldly confessing “Mujhe Tumse Mohabbat Hai” (I am in love with you), Nanda is subtler and more reserved, almost as if dancing for her own pleasure, musing that she has lost her sleep since meeting her beloved in her thoughts: “Milke Khayalon Mein Hi Apne Balam Se / Neend Gawa Li Apni Maine Kasam Se.”

In ‘Baahon Mein Chale Aao’ from Anamika (1973), Jaya Bhaduri exudes innocent charm, candidly inviting her beloved to embrace her. She teasingly rebukes a bewildered Sanjeev Kumar, questioning how he can spurn her affection after initiating it himself:

Chale Hi Jana Hai

Nazar Chura Ke Yoon

Phir Thaami Thi Saajan Tumne

Meri Kalaai Kyun

If you were going to leave after

Only stealing a few glances

Then beloved, why did you even

Hold my wrist

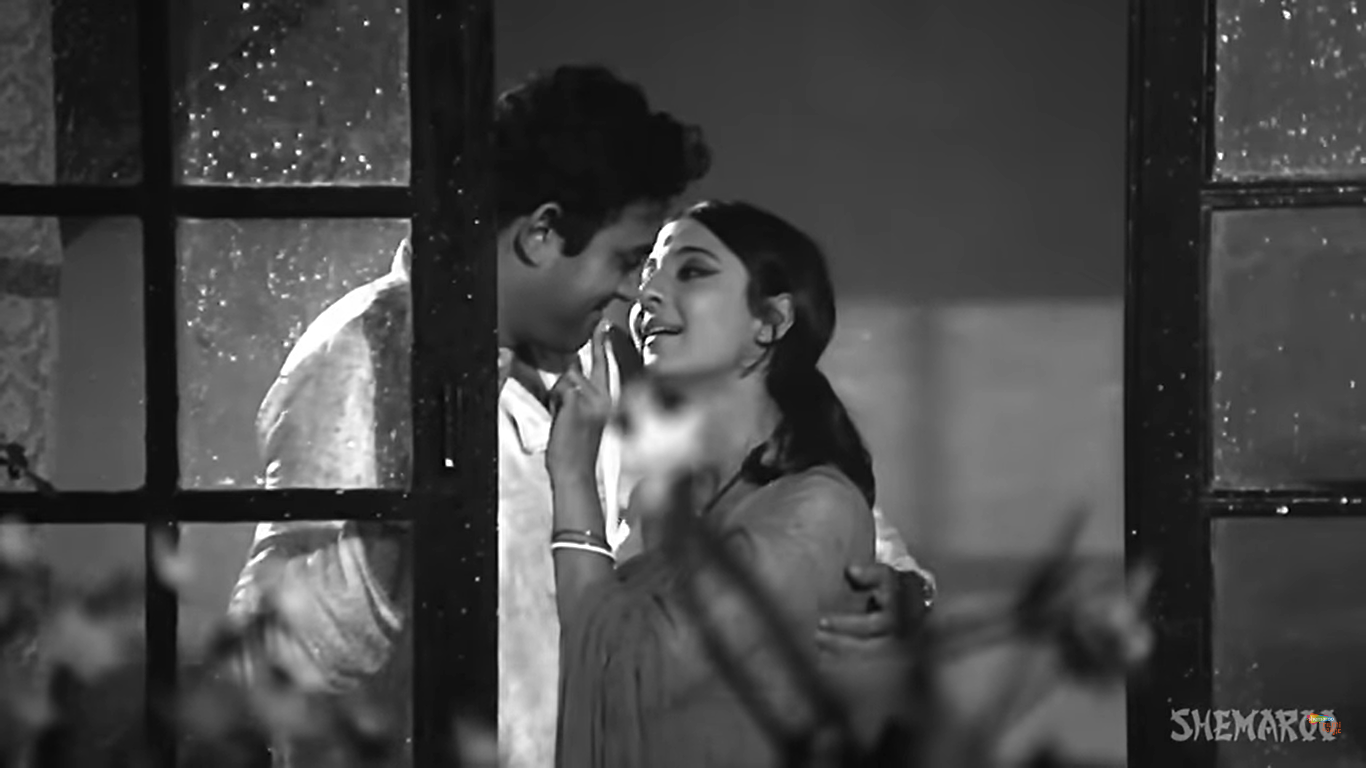

‘Chhup Gaye Saare Nazaare’ from Do Raaste (1969) presents a similarly innocent display of physical affection through a playful push-and-pull dynamic. Two lovers cozy up to each other while the rain pours down. Although Mumtaz averts her face when Rajesh Khanna tries to steal a kiss, she initiates intimate contact in a subtler way, caressing his feet with her own.

No discussion of Hindi film songs would be complete without mentioning those that feature dancing and singing in the rain. The magic of the monsoon is a recurring motif in songs that evoke the shringara rasa, the erotic sentiment or ecstasy of love as defined by the ancient aesthetic theory of rasa.

In ‘Haaye Haaye Ye Majboori’ from Roti Kapada Aur Makaan (1974), Zeenat Aman turns up the heat, openly seducing her lover and confessing her physical desire while dancing exuberantly in the rain:

Yeh Mausam Aur Yeh Doori

Mujhe Pal Pal Hai Tadpaaye

This weather and this distance

Torments me every moment

In a rain-soaked space where only she and her lover remain, she can unabashedly confess how long she has been yearning for him:

Kitne Saawan Beet Gaye

Baithi Hoon Aas Lagaye

So many monsoons have passed

While I was waiting for you

In ‘Kate Nahi Katte’ from Mr. India (1987), Sridevi matches Anil Kapoor’s passion with equal vigor, boldly admitting her love:

Lo Aaj Main Kehti Hoon

I love you

It’s fair to say that song sequences act as a parallel narrative of sorts, a performance within performance, that propels the narrative forward while offering a peek into the characters’ longings and inner conflicts that may not be explicitly addressed in the main plot. These musical moments become a safe playground for women to explore their sexuality and self-expression freely, all while the regular plot chugs along outside this magical bubble.

It is through these songs that women appear not only as the object of desire but also become active pursuers of their own desires—whether it’s the shy damsel coyly chasing her beloved or the bold seductress openly propositioning her lover. Such displays of female agency would often be unthinkable in the regular flow of the story.

Take, for example, Meena Kumari’s Chhoti Bahu in Saheb, Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962). As the daughter-in-law of a zamindar family, she is bound by the rigid expectations of Bengali society, enduring a lonely existence while yearning for the attention of her unfaithful husband. The evolution of her desires and longings is expressed primarily through songs.

The soulful ‘Piya Aiso Jiya Mein’ begins with the demure yet sensual Chhoti Bahu preparing herself elaborately to meet her beloved husband, crooning about how he has stolen her heart:

Piya Aiso Jiya Mein Samaye Gayo Re

Ke Mein Tan Man Ki Sudh-Budh Gawan Bethi

Beloved you’ve entered my heart in such a way,

that I lost consciousness of my very self.

However, her intense longing is unreciprocated, as her husband prefers the company of a courtesan over his own wife. Chhoti Bahu’s deep romantic and erotic yearnings fester, and in ‘Na Jao Saiyaan,’ we meet a very different version of her. Now drunk, she expresses her desires more boldly, swaying and writhing on her lavish yet empty bed in a manner rarely associated with the demure damsels of Hindi films.

Na Jaao Saiyyaan, Chhudaa Ke Baiyyaan

Kasam Tumhaaree Main Ro Padoongee

No longer yearning quietly, she demands attention, combining a wife’s devotion with a courtesan’s allure. She confronts her husband directly, refusing to be dismissed. The lyrics grow increasingly sensual, with references to dishevelled hair, smudged makeup, and intoxication:

Ye Bikhree Julfein, Ye Khiltaa Gajra

Ye Mahakee Chunaree, Ye Man Kee Madeeraa

The phrases are steeped in both her uncontainable desire and her overwhelming anxiety of being rejected, with the plea, “Na Jaao Saiyyaan” (don’t go, my love) transforming into the bold assertion, “Main Tumko Aaj Jaane Na Doongi, Jaane Na Doongi” (I won’t let you go today, won’t let you go). Sung in Geeta Dutt’s lilting voice, these songs were groundbreaking for their portrayal of a married woman’s sexual desires toward her husband.

A more delicate facet of marital intimacy is revealed in ‘Meri Jaan Mujhe Jaan Na Kaho’ from Anubhav (1971), allowing the audience to witness a tender, intimate moment on a rainy night. Basking in the glow of a gentle kiss, Tanuja sings to Sanjeev Kumar:

Honth jhuke jab honthon par

Saans uljhi ho saanson mein

Do judwa honthon ki

Baat kaho aankhon se

When your lips are near mine

And our breaths intertwine

Tell me what our lips want to say

With your eyes

In ‘Aaja Sanam Madhur Chandni Mein Hum’ from Chori Chori (1956), the dream-like ethereal ambiance gives Nargis the freedom to voice her longing, asking Raj Kapoor to steal her away from her loneliness:

Kehta Hai Dil Aur Machalta Hai Dil

More Saajan Le Chal Mujhe Taaron Ke Paar

Lagta Nahin Hai Dil Yahan

My Heart Speaks And Dances My Beloved,

Take Me Across The Stars

I Am Lonely Here

These songs carve out a unique space in 20th century Hindi cinema where women can lay bare their desires or plead with their lovers and even engage in seduction without risking being robbed of the chastity and virtue that affords them their position in the story. A dream-like atmosphere emerges from these interludes where social norms can be bent and expectations turned on their head. By occupying a separate, more fluid dimension within the film, song sequences become a site for diving into desires and fantasies that the main narrative might shy away from.

Interestingly, these songs often turn inward, focusing on how the women themselves feel in their desire for their beloved, rather than centering on the beloveds themselves. While Hindi cinema frequently features songs that appreciate or objectify women through the male gaze, there is a notable absence of songs that celebrate male beauty from a female perspective.

While Hindi cinema has seen, on rare occasions, a few songs catering to the female gaze—like ‘Dard-e-disco’ from Om Shanti Om (2007) serving up its leading man on a golden platter—it’s ‘Dreamum Wakeupum’ from Aiyaa (2012) that really flips the script. This item number turns the tables by presenting both the man and woman through equally stylized, sultry portrayals. Prithviraj Sukumaran’s revealing outfits spotlight his physique, challenging the usual item song dynamics and putting male sensuality center stage, while Rani Mukherjee openly sings about his “thundering thighs”. The whole sequence is a celebration of female desire and fantasy, making the man the object of visual pleasure for a change.

However, with an increasing presence of female filmmakers and songwriters in the industry, perhaps we will soon hear leading ladies singing about ‘Sagar Jaise Ankhonwale‘ or ‘Yeh Reshmi Zulfen’. But one thing is for sure — when this shift does occur, we will see fewer songs fixated on thin waists or fair cheeks and more on the allure of strong forearms or baritone voices.

Advani, Nikkhil, director. Kal Ho Naa Ho. Dharma Productions, 2003.

A.K Music. “Raat Akeli Hai – Song | Jewel Thief (1967).” YouTube, 15 Mar. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Su4vvd2thG8.

Curtiz, Michael, director. Casablanca. Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc., Distributed by the Voyager Co, 1942.

Goldmines Gaane Sune Ansune. “Katra Katra Milti Hai Katra Katra Jeene Do | Asha Bhosle | Ijaazat 1987 Songs| R. D. Burman | Rekha.” YouTube, 10 Oct. 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=PZzK3CVzLKo.

Shemaroo Filmi Gaane. “Chhup Gaye Saare Nazaare (HD) | Lata Rafi Karaoke Song | Do Raaste | Rajesh Khanna | Mumtaz.” YouTube, 14 Apr. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kjkg9NlUpeM.

—. “Lyrical: Yeh Sama, Sama Hai Ye Pyar Ka – Jab Jab Phool Khile – Shashi Kapoor – Nanda -Bollywood Song.” YouTube, 7 Feb. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=-BPW6TKZEe4.

—. “Meri Jaan Mujhe Jaan Na Kaho – Sanjeev Kumar – Tanuja – Anubhav – Geeta Dutt – Old Hindi Songs.” YouTube, 7 Dec. 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=F6FkVPOMtvM.

SuperHit Gaane. “Aaja Sanam Madhur Chandni Mein Hum 4K | Chori Chori Song in Color | Raj Kapoor | Nargis.” YouTube, 10 June 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=msRBZuoerGo.

—. “Baahon Men Chale Aao 4K – Lata Mangeshkar Romantic Song – Sanjeev Kumar, Jaya Bachchan – Anamika.” YouTube, 4 May 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=_uzRGxe0LUs.

—. “Haye Haye Yeh Majboori Song 4K – Lata Mangeshkar – Zeenat Aman, Manoj Kumar | Roti Kapda Aur Makaan.” YouTube, 10 Apr. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=XTrWegr2OkY.

—. “Lag ja gale ki phir ye haseen raat ho na ho Video Song | Lata Mangeshkar | Woh Kaun Thi Songs.” YouTube, 15 Dec. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2fgw1Oqz28.

—. “Na Jao Saiyan Chhuda Ke Baiyan in COLOR 4K – Geeta Dutt – Meena Kumari | Saheb Biwi Aur Ghulam Songs.” YouTube, 20 Apr. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=8tXfsxL2zVg.

—. “Piya Aiso Jiya Mein Samaye Gayo Re in COLOR 4K – Meena Kumari | Geeta Dutt – Saheb Biwi Aur Ghulam.” YouTube, 22 June 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=37C01bClMBs.

—. “आइये मेहरबाँ : Aaiye Meherbaan [4K] Video Song | Asha Bhosle | Madhubala, Ashok Kumar |Howrah Bridge.” YouTube, 28 Dec. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=go4ixEgnecg.

Tips Official. “Ek Haseena Thi Ek Deewana Tha – Lyrical | Karz | Rishi Kapoor| Kishore Kumar, Asha Bhosle|80’s Hits.” YouTube, 28 May 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjrRwMAuNRU. T-Series Bollywood Classics. “Kate Nahin Kat Te -Video Song | Mr. India | Kishore Kumar, Alisha Chanai | Anil Kapoor, Sridevi.” YouTube, 23 Apr. 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=9FjuBvzF1E4.

T-Series. “Dard E Disco Full Video HD Song | Om Shanti Om | ShahRukh Khan.” YouTube, 26 Apr. 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=cKs83ZQxYKA.

—. “Dreamum Wakeupum Aiyyaa Full Video Song | Rani Mukherjee, Prithviraj Sukumaran.” YouTube, 8 Nov. 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=AQeC89lO2w0.

Singh, Shivendra. “‘The Heart Has Gone Out’: The Evolution of Hindi Film Songs – and India.” The Wire, 31 Mar. 2024, staging.thewire.in/film/

the-heart-has-gone-out-the- . Accessed 14 July 2024.evolution-of-hindi-film-songs- and-india Sengupta, Saswati, et al. ‘Bad’ Women of Bombay Films: Studies in Desire and Anxiety. Springer Nature, 2019.

Dwyer, Rachel. “Kiss or Tell? Declaring Love in Hindi Films.” Love in South Asia: A Cultural History, edited by Francesca Orsini, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 289-302.

- Shirsha Ghosh

Shirsha Ghosh (she/her) graduated from Delhi University in 2022 with a Master’s degree in English Literature. She holds a Certificate in Editing & Publishing from Jadavpur University and is currently a publishing professional. Though her main interests include gender studies, folklore, cinema, and popular culture, she is curious about everything from art history to anime, and this eclectic mix often finds its way into her writing. When not immersed in books or crafting her own pieces, Shirsha can be found hopping from one hobby to another.