Queering Performative Photographs: A New Aesthetics of Gaze and Desire

- Anna Lynn

Eve Sedgewick in “Here and Now” has a haunting line for those engaged in queer studies. She says, we remember our “promises to make invisible possibilities and desires visible.” In a way, I encounter these performative photographs as a part of that journey. This desire is an intense bodily want, because it feels unattainable. Because, as queer, we forage for visible proof of our natural ways of being. And seeing becomes a first step to being. I discover Truth Dream first, on a sunny Tuesday winter afternoon at the Bangalore International Centre. As part of the research journey triggered by Truth Dream, I hunt for photographic possibilities of dreams, desires and dressing-up. And that is how Tejal Shah’s Hijra Fantasy series finds me, around six months from the photo-exhibition.

As I walk myself to the Truth Dream traveling exhibition, I am aware it is part of Sedgewick’s promise. I am not prepared for the reactions I hold. The bodies I see, their smiles, their seriousness, their joy and their stories that create it, are a part of the same promise. I know somewhat intimately of one – Revathi, because I have read her autobiography – The Truth About Me: A Hijra Life Story. Her presence in this photo-exhibition is a continued encounter with her narrative of survival. There is a thin line between truth and visibility, between dreams, desires and performance, between the aesthetics and the labour born of unwritten dreams. Even within an illusory photograph, you are given the gift of imagining yourself otherwise – defamiliarising yourself from the labels pinned on you by birth – girl, woman, and then your own – non-binary. How is this queer imagination created? Why is the performative mode used with the photographic medium? And what happens when they collide? Through this analysis of the Truth Dream photo exhibition and Tejal Shah’s Hijra Fantasy series, I propose that these performative photographs create a queer aesthetic that hinges on acts of recreation. However, at its crux, I am attempting an answer to the larger concern – why does this matter? Why do we need to see these desires at all?

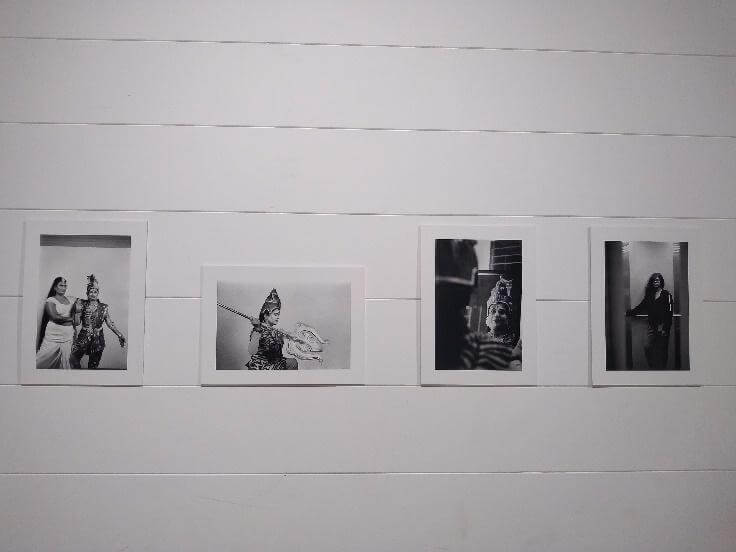

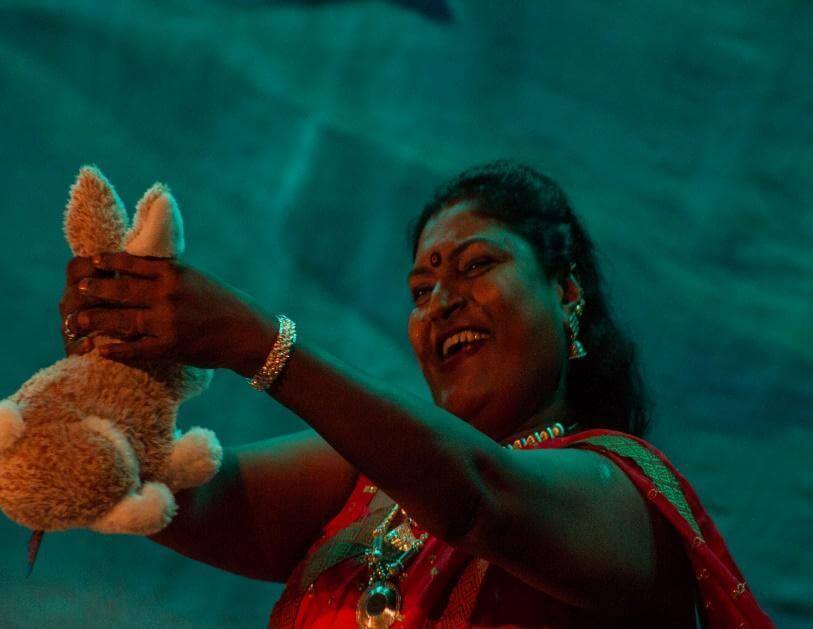

In the foyer of Bangalore International Centre, there were twelve sets of performative photographs as the primary part of Truth Dream. It is an art project initiated by Maraa —an arts and media collective based in Bangalore—and Payana, a community-based organisation working for the interests of sexual and gender minorities in Karnataka. I have missed the opening day performance – where the twelve models from the queer communities donned the personalities they embody within the photographs to a medley of song and dance. Each community model has chosen to perform characters significant to their queer journeys: Revathi dons the garb of Andal, while Bhanu transforms into a Courtesan. Bernie chooses to perform as a Drag King while Saravana/Shakila dons the attire of a Bharatnatyam Dancer. As a spectator, I joyfully move across these performative visions.

The community models also share how intersectionalities of caste and class have influenced their choices. Bhanu expresses that although she has given many performances, she has never had the luxury of donning expensive costumes or jewellery. Similarly, Saravana/Shakila shares that they were unable to attain their dreams of performing as a Bharatnatyam Dancer because they had to discontinue their studies due to poverty (Truth Dream Crowdsourcing Videos).

Theories of gaze ascribe male gaze and power play into visual significations of gendered representations (Mulvey 1975). I enter this world of subversive gaze through Revathi’s memories; I remember her narrative of how she was teased and punished as a child for performing traditional tasks assigned to girls/women – sweeping the front yard, drawing kolam, wearing flowers in her hair and dancing (Revathi 2010, 3,10). Within the performative photograph series, she is resplendent in love and longing for the Lord. Andal, glorious in her desire for Perumal. That she travels from a past of othering to this present of realising a childhood fantasy fills me with quiet (queer) joy. If she has travelled this far, we have hope yet.

So it is this language of performance that creates disruptions to normative representations of desire (largely heterosexual and binary), power (usually portraying the woman or queer person as a sexual / strange object) and identity (marginalising our chosen existences and experiences). Through these embodied performances, a part of this subversion of gender and sexuality is attempted. But what lies at the centre of this queer reclamation?

Perhaps it lies in the acts of collaboration. The photo exhibition project invited members of the sexual and gender minority community into the performative process. Each community chose to recreate a character from popular visual culture/mythology with whom they most closely associate their histories of gendered othering. In performing the characters, they were living their unwritten dreams.

On the definition of ‘ Truth Dream ’, Chandini, one of the founders of Payana says, “The body grows old, not our feelings or dreams.” All the members are above the age of 50 and identify across the spectrum as trans women, trans men, gender-neutral and kothi. They hail from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. The twelve sets of photo exhibits, distributed between the first and second floor of BIC, read as a motion series. In seeing them, there is a reclamation of heteronormative narratives of desire and identity. Ideals of timeless beauty are given a new meaning. The individual sets are seeped in the play of light, shadow, sound and music. Beside each photo-montage is a QR code, which upon scanning will play a popular song from the film that the subject of the respective photographic series embodies. Animating the photographs to the music lies within the fantastical powers of the spectator. In a Butlerian sense, desire lives through these performative acts (Butler 1988, 523).1

In their essay on Performative Acts, Butler also mentions an indispensable aspect of the state of embodiment – that we are bodies that incorporate or appropriate culture and history as part of our consciousness experience of inhabiting a body (Butler 1988, 521). However, there is another obvious side to this incorporation – of finding mirrors to one’s identity. Lacanian psychoanalysis is the first to explain this relationship between the recognition of the mirrored self, and our expression of unconscious desires through language. However, for queer lives, these mirrors to personal desires are disruptive from the early moments of visual recognition. A. Revathi narrates the story behind her choice to embody Andal for her performance – “After watching the film, Thirumal Perumai (1968), I thought that if I was devoted to Perumal, I would get married. After many years, neither did Perumal come, nor did I get married.” In her avatar as Andal (a character in the film who shares an intimate relationship with Perumal), there is an intense gaze of stoic power and gentility at the same time. One holds her gaze, as a moment of benediction.

It is by no means an easy feat to enter the garb of a character denied to you. A way of living, erased from your chosen form of existence! And perhaps this process of appropriation within culture is no more disorienting than within queer bodies. Revathi’s narrative behind her performance as Perumal for the Truth Dream project is indicative of this personal history of disorientation. A history of denial, erasure and othering. Against this history, it becomes an act of rebellion to perform an identity pushed to the margins (Butler 2007, 201). Another way of seeing. Another vision of personal history.

These attempts at enabling visibility insinuate the presence of labour. In the creation of Tejal Shah’s photo prints, their Hijra collaborators’ narratives come through – their experiences of being shunned by a society and forcing them into sex work and asking for alms (Jiwani and Shah 2010)2. There are accordingly two kinds of labour here – one, the labours for survival (sex work and begging for alms) as a result of othering by society, and two, the personal labour of extricating from a marginalised past. In collaborating with artists for the performative photographs, both come into play for the members of the gender and sexual minority community.

The characters chosen for embodiment demonstrate a clear engagement with the notion of the popular (antithetical to highbrow culture that further denies the existence and labour of sexual and gender minorities, relegating them to the lower class). Thus, in Truth Dream the models themselves question impositions of class and caste in their portrayals of cabaret dancers, drag Kings, gods and goddesses, village belles and characters from film – Shakuntala, Andal and others.

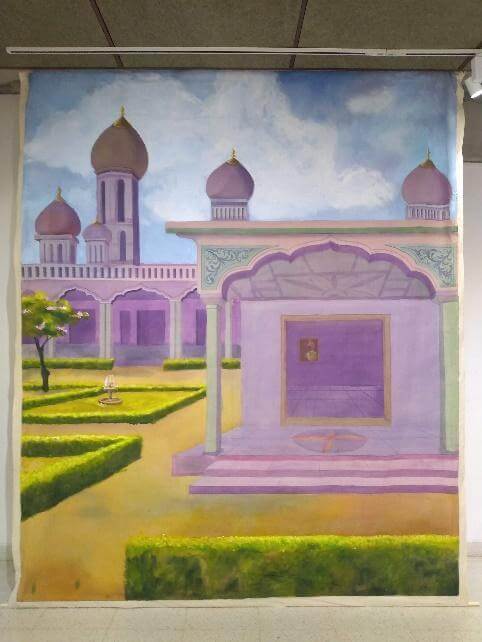

Truth Dream is a collaborative process – members from the queer community, and producers, make-up artists, curators, concept designers and others come together to create this visibility. So are Tejal Shah’s performative photographs from the Hijra Fantasy series. Both the projects make an appeal to the unreal to utter and reveal marginalized truths of lived experience, unexpressed dreams. In the photo exhibition, the trails of collaboration are present in the form of photographs and videos documenting the process of transformation, a book titled Kannadi and the large tapestry paintings hung by the backdrop of each floor’s staircase.

In Tejal Shah’s photo-prints – You Too Can Touch The Moon and Southern Siren, queer desire deliberately inserts into the popular narrative – of motherhood, of romance, of bedtime story, myth and filmic courtship. And this brings us to negotiations between the medium, performativity and queer desire. Performance embodies disruptive expressions of identity and with it power, desire and normativity. The photograph asserts this disruption on several levels – primarily, the ubiquitous form of the gaze: of being seen, and of showing. Following this are the possibilities inherent in the nature of the medium – photography is in essence a repetition, a fabrication, a performativity of its own. When desire becomes the fuel of insertion, a new language of expression is created. It is by nature subversive – gender performativity caught in time.

Further, an interweaving of myth and desire is enabled through the art of this performative photograph. Laura Mulvey aptly terms the ‘cinema’, a phantasmagoria – where elements of fantasy, illusion, the fantastic and the real narrate themselves (Mulvey 1996, 16). We realise how the gaze of desire enters our visual vocabulary, through the cinematic form. It is also the source of our own personal fantasies of performance and embodiment. Ways of being that follow ways of seeing. It is only natural then that the language of subversion plays through this form of repetition. In Truth Dream, these characters are varied. The mythological figure makes an entry in the garb of characters like Shakuntala and Ardhanarishvara. Some manifest their desires of characters from 60s cinema, including heroines coy in love and longing, dancers lost in the thrall of palace courts, village maidens dreaming in gardens or pathways, cabaret dancers, film stars and queens occupying spaces with power and grace.

In comparison, Shah’s project is a deliberate insertion to bend the rules of our gendered gaze into popular cultural representations of say, Yashodha and Krishna or Southern film song sequences. On the other hand, Truth Dream intends to enter the narrative and appropriate the gendered characters into assertive queer identities. Their processes are different, even intents to an extent, but both play with the ‘boredom’ of heteronormative representation. They not only question the rules of desire and how we are shown them in consuming popular cinema or stories, but create multiple divergences to the sites of disrupting gender and sexuality norms.

When an artist chooses a medium like photography, they are building a fable, yes! And there are deliberate choices that go into its creation. In addition, there is the idea of time and memory that is played with (Berger 2015, 56). When gender and sexuality become the core of that fable, there is a disruption. This disruption is begotten from an experience of disorientation and flows towards creating another. It is a peculiar nature of queerness that Sara Ahmed elaborates upon: “disorientation involves failed orientations” (Ahmed 2006, 160) As a result, the body is moved into presenting itself through “defamiliarisation” or strangeness of that which was familiar. It is only natural then, that these disorientations centre personal experiences within their visuals. In this way, creating an alternative gaze – queering visions, and opening up to possibilities for seeing!

A queer aesthetics of desire and assertion is born from the very temporal transferability of the medium, towards being seen and heard. And in seeing and hearing this defamiliarised/ queered popular motif, in listening to the Kannada and Tamil songs and lingering by the performative stills, in chancing upon Tejal Shah’s print of Southern Siren a queer mimicry of an old filmic dance sequence, there is an emotion of being moved (Ahmed 2014, 206). There is a smile titled on the knowledge that these photographs make our dreams, formerly alternate and marginalised – true and centred. I like to think they reside in the million Maheshwaris at the centre of the rose in Southern Siren, in the lone moon of You Too Can Touch… and in the speckles of glitter and shine that adorn the faces of our models in Truth Dream. They are infinite – possibilities that memorialise personal pasts and define future gaze. It matters, for me (and perhaps others like us), because showing/seeing can be the first step to being.

Photograph Credits

Truth Dream: Launch Event Photographs by Javed Iqbal

Exhibition Photographs by Anna Lynn

B&W photographs at Gallery by Rudra Rakshit Saran

Colour photographs at Halls by Jaisingh Nageswaran

Hijra Fantasy Series: Tejal Shah

Endnotes

- Judith Butler in “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory” explains how gender is constituted through “performative acts of repetition.” This implies that within these photographs, through acts of repetition (be it binary body language or dressing), gender as a performance is presented to the spectator.

- In the essay “HIJROTIC: Towards an Expression of Desire a critical introduction to Tejal Shah’s Hijra Fantasy Series”, the author Subuhi Jiwani describes how narratives by the Hijra models serve as Tejal Shah’s inspiration behind the series.

Ahmed, S. (2014). “Afterword: Emotions and their Objects.” In Ahmed, S. The Cultural Politics of Emotion . Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 204-233.

—. (2006). Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Berger, J. (2015). “Uses of Photography.” In Berger, J. About Looking. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 48-61.

—. (2008). Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Classics.

Butler, J. (2007). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

—. (1988). “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal, 40(4), 519-531.

Chandni. (2021). “Truth Dream.” Maraa and Payana, Bangalore. Photography.

Jiwani, S. and Shah, T. (2010, January 1). “HIJROTIC: Towards a New Expression of Desire – A Critical Introduction to Tejal Shah’s Hijra Fantasy Series.”. Mayday Magazine. https://maydaymagazine.com/hijrotic-towards-a-new-expression-of-desire-a-critical-introduction-to-tejal-shahs-hijra-fantasy-series-by-subuhi-jiwani/. Retrieved on 28 April 2021.

Maraa. (n.d.). Crowdsourcing videos. Facebook. https://ar-ar.facebook.com/Maraa-a-media-and-arts-collective-135629861736/videos/truth-dream-is-a-photo-exhibition-tracing-the-dreams-and-lived-experiences-of-se/1277543742696772.

Mulvey, L. (1996). Fetishism and Curiosity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

—. (1975). “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, 16(3), 6-18.

Revathi, A. (2010). The Truth About Me: A Hijra Life Story. Gurgaon: Penguin Random House.

Shah, T. (n.d.). Southern Siren. Thomas Erben Gallery, London. Photograph.

Shah, T. (n.d.). You Too Can Touch The Moon. Thomas Erben Gallery, New York. Photograph.

- Anna Lynn

Anna Lynn is a research scholar of comparative literature at The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad. Prior to this, she was an Assistant Professor of English at St. Joseph’s College of Commerce, Bangalore. Her research area explores the nature of gender through a queer feminist lens, applied to postmodern Indian art practice. Her areas of interest include women’s writing, art and cinema. The anxieties of a queer heart are a constant muse and as the Woolfian stream passes, she presses watered images into writing. You can find her work on The Chakkar, Gulmohur Quarterly, Live Wire and Catharsis Magazine.